Western Worldview- And how it makes our brains tiny

( I dedicate this blog title to a Claremont alum friend who approved it on IG and she’s been sick, so she gets the blog title she wants)

We Don’t Even Know It’s There

Here’s the thing about worldview—we typically don’t realize we have one. Its the container in which we move. We may be aware of moving from one part of the container to another, but we remain unaware of the container itself, the way it is shaping how we move and where we move. So when it comes to theology we might change our theological opinion from

not supporting to supporting women in leadership,

or not affirming to affirming our queer kin,

or not talking about race in church to assuming it should be addressed from the pulpit

But we rarely step back to examine our assumptions about theology itself—the assumption that theology is primarily an intellectual exercise or something to be debated. We rarely question whether we’re even asking the right questions; instead, we argue over the answers. This happens because we aren’t aware of how the Western Worldview is creating a container for how we approach theology.

Much of this stems from not recognizing how our worldview is being formed in the first place. Language is a powerful example.

Language doesn’t just reflect reality; it shapes how we experience it. Take land, for instance. When we refer to it as a “natural resource” or speak of “ownership,” we’ve already placed it within a framework of extraction and possession. Without realizing it, we’re reinforcing a capitalist lens that reduces land to something to be used rather than something to be in relationship with.

But what if we learned to speak about land as a relative? Relationship and interrelatedness with the community of creation are embedded in many Indigenous languages. For example, in the Lakota language, there is a phrase, Mitakuye Oyasin, which translates to "All My Relations" or "We are all related.” And I must credit Lenore Three Stars for her teaching on this topic. The phrase holds a worldview—one of deep relationship with the land, and one of respect, mutuality, and responsibility.

This difference in language highlights another point: how worldview shapes not just what we say, but how we think. If our words shape our reality, then a language that centers relationship fosters a worldview of interconnectedness. But what happens when a language is built around the individual?

The Limits of Individualism in Language

English is obsessed with the individual.

And here’s another way English centers the individual: we capitalize “I.” Think about that. We don’t HAVE to capitalize “I.” It’s a choice. Meanwhile, other languages don’t do this. In Korean, names aren’t capitalized, its not even an option. And your last name comes before your first name. Think about how that holds meaning and value. You’re family name comes before your personal name.

But English? English props up the individual at every turn. It capitalizes the self and doesn’t have space for a collective “you.”

Case in point: There’s no real collective “you.” In the South, folks say “y’all.” Other languages make a clear distinction between “you” the individual and “you” the group. But English? It collapses everything into the singular. And that has major implications—especially when reading the Bible.

Most of the Bible isn’t speaking to “you” personally. It’s addressing entire communities—nations, cities, the people of God. But because English is so individualistic, Western readers shrink everything down to personal promises, personal morality, personal responsibility. Suddenly, collective accountability gets erased, even though the Bible is FULL of it.

And when that’s the container that we are given to make meaning of the world, and of the Bible, it has some troubling implications.

It means that even though huge portions of the Bible- Elder Testament and New Testament- are talking to collectives- those of us who speak English and have been shaped by the Western worldview turn everything into an individual conversation with God. And interpret sin as something that an individual does and an individual is held accountable.

So now when folks want to talk about the collective sin of slavery in the United States, the sin of genociding Native Americans, the sin of greed by corporations, the sin of ongoing corporate greed in many forms- the church says it has not place in the church, and continues to fixate on individual sin.

Because of the Western worldview—its deep-rooted individualism, the limitations of its language, and the way Western Christianity has been co-opted by empire—theology has been reshaped to serve the agenda of the U.S. Empire. Here in the United States, white Christian nationalism has become a tool of empire, and empire is not interested in being held accountable for its sins. And I’m intentionally using the language of sin here.

The Bible is deeply concerned with how nations use their power. It is interested in holding them accountable, and naming sin for what it is. But empire doesn’t want a theology that challenges it. It wants a theology that allows it to do whatever it wants without accountability. It wants a theology that allows it to do as it pleases while being punitive toward individuals.

Theolgies of empire are not really interest in individual holiness—just look at Trump. It is interested in power- just look at Trump. It exists to police marginalized people it perceives as a threat while making accountability for the very worst perpetrators of violence impossible.

When you carry the Western worldview’s obsessive individualism, unbridaled capitalism, and American Christianity’s relentless fuckboy allegiance to empire— you end up here. Right where we are in 2025.

* I must always credit Dr. Randy Woodley, Edith Woodley, Lenore Three Stars and many of my professors from the Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies with introducing me to this topic and to Indigenous worldview. I can not credit them for each idea they have given me, because they have throughly shaped by understanding of both the Western Worldview and Indigenous Worldview so thoroughly

Jesus is Born

Even with all my critiques of institutionalized Christianity, the evil of Christian nationalism, and all the church hurt I see on a daily basis, I still believe. I still believe that the birth of Jesus means something, to me, to women of color, and to the world.

The reason I like Advent so much, is that it takes me back to a moment before all the distortion

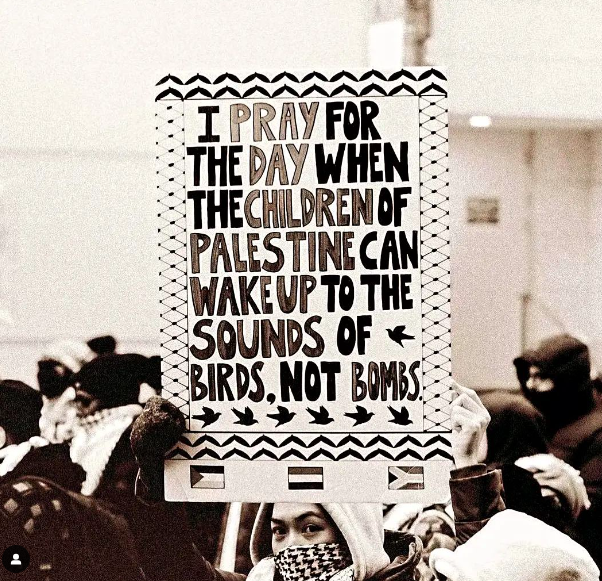

And this year, as we consider the reality that the city of Bethlehem has been under military occupation since 1967 and that Palestinians born in Bethlehem are born into apartheid, I am reminded again that we need the birth of Jesus to mean something in this world.

Reverend Munther Isaac a pastor in Bethlehem, occupied Wester Bank, has preached repeatedly that “If Christ were to be born today, he would be born under the rubble and Israeli shelling.”

Jesus gets called the Prince of Peace a lot this time of year. But his followers are so often known for violence, colonialism, and militarism.

That’s why Advent is such a sacred practice. Each week during Advent, we are given the invitation to rewind. To wade through thousands of years of empire and distortion. I imagine a baby born to an astute and thoughtful young Jewish woman, the astrologers who followed the stars, the angels who were filled with a song. I let my imagination breathe with what that moment meant. I let hope pull me back to center. I think about the fact that Creator came because God so loved the world- not because God wanted to judge humans into oblivion. That the birth of Creator was birthed out of love for all of humanity and all of creation. And the way of Jesus was not militarism, or empire, authoritarianism or coercion. It was vulnerability, humanity, relationship, community, and tenderness.

It was a life in solidarity with refugees, the poor and displaced, those thrown around by the the egos of insecure leaders, and the weight of empires.

Jesus is born.

Peace on earth.

A prayer for our times.

Community

Not giving up on it, even though its tough and we’ve all been wounded, and sometimes its a hot mess.

I love community. I’ve been married for 17 years and for at least 10 of those years we lived with people or had people live with us. I think living in community is great. I love working on a team. And I love creating community in cohorts.

But…

And we all know this.

Community can break your heart.

Over the last twenty years I’ve watched countless painful community explosions as leaders fail, as church’s split, as folks leave over race, politics, and abuse. I’ve seen queer and trans kin ousted by faith communities. Families going no contact.

And closer to home I’ve had hard conversations with dear friends where we’ve wounded each other. I’ve watched cohorts screech to a halt over group dynamics, difficult conversations, mismatched personalities, and as disappointments surface in painful ways.

A delicate part of building community in Liberated Together is the reality that everyone has very recently been wounded and disillusioned by community. We trigger each other, we touch on unhealed wounds. Yes, we also heal each other, and laugh, and learn, and carry each other gently. But the nature of all good things is that whatever amount of good they can do, they have the power to do the same amount of harm.

Christian community is often discussed in very idealized terms. I’ve lost count of the number of sermons I’ve heard on Acts 2 community. And I speak often on my favorite snapshot of community, which is the time Mary spends at Elizabeth’s house at the start of the book of Luke. The season of Advent is about the hope that something new can be birthed in the midst of darkness and violence. And I believe that deeply.

But I also know that that the new thing will be birthed by a bunch of wounded people, who never learned to do conflict well in their families, and who have rarely seen leaders respond well to feedback. Folks who got into justice work because of experiencing some sort of trauma. A community of wounded and traumatized folks, who are brilliant and caring, and have never seen the thing they are hoping for.

It’s complicated.

Idealized visions are motivating. Idealized versions of people, of movements, and of community are appealing. But they won’t get us where we need to go. Learning to do conflict, learning to communicate in the midst of this dumpster fire country, learning to own when our own trauma is steering the ship, saying sorry, talking to folks directly instead of talking about them to others- these are all social justice skills. These are all part of movement work. We have to learn to treat each other in the ways of the world we are trying to build.

And I knowwwwww, believe me I know. That we would all love to rally around a glorious vision of liberation more than we would like to learn to resolve conflict with this person we are getting to know, who low key annoys us and triggers the shit out of us. But figuring out how to stay in community with a bunch of wounded people with a dream, might be the most radical politic of all.

And this loops back to the reflection of week one, holding on to our humanity. Holding on to our humanity means that we make time and space for the unglamorous and seemingly unproductive work of figuring out how to stay in community with each other. We fight the tendency to treat people and relationships as disposable.

There is no version of building a new world where we don’t break each other's hearts again and again. And the courage to keep going and hoping in the midst of that reality is what I ponder in this season, as I look into the sky for a star to guide me.

Choosing Vulnerability

Advent- Week 2

Human babies are wildly vulnerable little creatures. We can’t hold up our heads. We can’t feed ourselves. We can’t walk for a long time. There is a little spot at the top of our heads where you can just poke our brains. Creator’s choice to arrive on earth as a human baby is still something I find quite mysterious and weird.

When I’m trying to shake loose from the interpretations of the Bible that I grew up with, I will step back and imagine Jesus’ life as performance art. The cross. The time in the desert. Making men feed thousands of women and children food. It helps my imagination activate and shake loose of the rigid interpretations I was given.

Being born as a baby is such an extreme and extended piece of performance art. Because it is so vulnerable. Jesus is so vulnerable. So at the mercy of his parents, the violent regime he was born under, the sicknesses of his time.

On March 21, 1965 at Carnegie Recital Hall, Yoko Ono staged a performance art piece called “Cut Piece” that has implanted itself into my imagination ever since I saw it. The premise is simple and well described here.

Ono near the beginning of the performance, which can be viewed HERE.

“Ono kneels on an empty stage with a pair of scissors in front of her. She says nothing except to outline the parameters of the performance- the audience members are welcome to come on stage one by one, cut off any piece of her clothing and take the piece back to their seat as a souvenir; the ending of the performance is decided by Ono in the moment. At first, the audience is hesitant- they come up and cut small pieces of her shirt or skirt and hastily return to their seats. However as the performance goes on, they become bolder. A man comes up and cuts off the front of her bra, and another cuts off the strap- at this point Ono brings her hands up to cover up her body. It continues like this for some time before Ono ends it.

This performance is meant to bring the audience into the work itself and have the artist and the audience interacting on an intimate level. Art to Ono is no longer about the artist giving the audience the established, final product. It is instead about the audience influencing the art.”*

When I think of the birth of Jesus, I think of Ono’s performance art piece. I can not watch her performance all the way through, because it makes me so uncomfortable. She is so vulnerable. And you can see that the audience members, and particularly the men, are enjoying the opportunity to cut off the clothing of this Japanese woman as she sits in silence. Her vulnerability is palpable and disconcerting.

Ono further into the performance piece.

I feel the same way about Jesus as baby. He is so dependent and vulnerable, it can be distressing to watch. “This performance is meant to bring the audience into the work itself and have the artist and the audience interacting on an intimate level. Art to Ono is no longer about the artist giving the audience the established, final product. It is instead about the audience influencing the art”. If you apply this description to Jesus’ choice to live as a human, it refreshes the intimacy of each human interaction.

Part of what has robbed us of this vulnerability is theologies of predestination and ideas like omnipotence. These theologies make every outcome a forgone conclusion, and Jesus is performing. But now he is not performing true vulnerability, he is pretending to have emotions, while living in the safety of forgone conclusions. This theology positions Jesus as an actor, one who is pretending to be a human, but is actually an all knowing being wrapped in a flesh costume. An actor who has read the whole play, and must now pretend that something is at stake.

The vulnerability of Jesus’ choice to become a baby, is obscured by institutional Christianity which has replaced vulnerability and Jesus’ humanity- with absolutes, rigid dogma, control, and an obsession with power. Institutional Christianity loathes true vulnerability.

We must now choose what we think is happening in the story. Is the art of Jesus’ birth that he is truly vulnerable and present and human? Or is it that he is very good at acting human, but inside it is all pretend?

I personally don’t accept the theologies that everything is set, decided, controlled, destined. I think they are patriarchal frameworks interested in control and too afraid of the possibility that Jesus was here, living the true authentic vulnerability of being a human.

Jesus doesn’t stay aloof. He doesn’t start as an elder, a teacher, a leader, or even just as an adult. He lets his tiny baby self be tossed around by terrorizing edicts to murder infants, the displacement of being a refugee in Egypt, the day to day need to be fed and nourished, cared for, and raised. Advent is the time to ponder the implications of this choice.

The world is a harsh place and it can make us callous. It can scar us and wound us. It can teach us to raise a thousand defenses to feel protected. But this bizarre and radical piece of performance art by Jesus, which leaves him at the mercy of the “audience” for decades, confronts that tendency. It speaks to that part of me that is wounded and tired. That part of me that would choose anger as the container for my hurt. Or shit talking. Or silence. It invites me to stay open and tender- even if it is only to witness Jesus choosing this radical and bizarre act of vulnerability.

*Article by Meg DiRuggiero on Bates.edu

Holding on to our Humanity

Week 1 of Advent

Dirty Dub Disaster by Lukas Feireiss

Justice work is the dream that all people would be given the opportunity to live, and to live with dignity.

Mass Incarceration

Hunger

Poverty

War

Domestic Violence

Racism

Name a system of injustice, and you will find a system that has decided that a particular group of people is less human and hence, disposable.

Palestinians, trans folks, dalit people, Indigenous women. Statistics and health outcomes will show that there is a system based on this group being deemed as having less value, being less human, and hence disposable.

This is not actually the hard part to grasp.

The hard part is recognizing that as we fight for justice, we often bring this system of disposability with us.

People who don’t agree with us are disposable.

People who don’t use a specific word are disposable.

People who aren’t focussed on the same issue are disposable.

I see this vibe cultivated on social media a great deal.

And it concerns me.

We can not build a new world, or a just world, or even a slightly better world, if all we are doing is changing around who we consider disposable. We have to find another way.

I spent most of the 90’s leading out of a model of justice work that was deeply white centered and uninterested in systemic change. So I understand the aversion to being overly relational. I’m deeply acquainted with the tendency to coddle the privileged. But rejecting an ethic of disposability does not have to become a toothless form of justice. We need to find a third way. And the truth is, we can not escape that justice work is not disembodied ideological work, it is human work. Not just the humans we are fighting for, but the humans are fighting against, and the humans we are hoping to convince.

If injustice is based on seeing some people as less than human, then justice work must be built on a commitment to honoring the humanity in all people, including those we are fighting. That doesn’t mean agreeing with all people, or coddling all people, but it forces us to confront our own internalized tendency to want to treat people as other and as disposable.

Grace Lee Boggs- Pioneering Chinese American Activist

In her book The Next American Revolution Grace Lee Boggs says, “I have been privileged to participate in most of the great humanizing movements of the past seventy years- the labor, civil rights, Black Power, women’s, Asian American, environmental, and anti-war movements. Each of these has been a tremendously transformative experience for me, expanding my understanding of what it means to be both an American and a human being, while challenging me to keep deepening my thinking about how to bring about radical social change.”

It is so telling that she speaks of each of these movements as “humanizing movements.” Capitalism, racism, white supremacy, patriarchy all move to dehumanize a certain group of people. We are often compelled and moved by those who are victims of these systems, but we must also consider our view those perpetuating the systems, and those who are sitting on the sidelines with ambivalence in the face of these systems. Will we let our rage against the systems lead us to dehumanize them?

For me, it is a sacred work to see the humanity in others, including those I deeply disagree with. The online space does not lend itself to this. I try to remember that the work is not just about what you believe, but challenging the the assumptions of how we treat those we disagree with. And as someone’s whose justice work is based on an ethic shaped by Jesus and Christianity*, I believe that every human is made in the image of Creator. And all of creation is in the image of Creator, and we are to treat it as kin.

I am not arguing for our queer and trans kin to stay in spaces that endanger them. Or other vulnerable and maginalized folks to endanger themselves. The place that I see this dynamic happening most often is by folks who are taking ideological stances, not folks who are directly impacted. White folks who won’t talk to other white folks anymore. Non-Palestinian folks cancelling people who aren’t speaking up in the way they deem correct. In my experience, people who are directly impacted by these systems of harm don’t tend to be the most rigid, it is those who put some form of their identity in being seen as a social justice person.

On both the progressive and conservative end of the spectrum, it is those who are least directly impacted, but have their identity rooted in their ideological purity, that are most rigid and cruel. The far ends of the spectrum end up running that is quite parallel.

Advent is a reminder that humans, in their tiny, vulnerable flesh containers are sacred. Creator came into humanity. Became a part of humanity. Embraced humanity by being a human. Colonial Christianity pretends that Jesus’ main focus was to punish, and we must reject this premise and all the ways it would seep into our lives. For the vast majority of his life Jesus simply lived, as a human, in his community, and in a body.

The invitation of Advent is to protect our belief in the sacredness of humanity. Not to let grief and trauma, war and violence, mold us into its image. It is a sacred practice to stay tender. To stay human. To see humanity in another person. To honor our own fragile human-ness.

As we enter into this season, how can we cultivate an ethic that sees the sacred humanity in each person?

*It makes me cringe to use the word Christian in reference to myself. Especially as I watch a white supremacist and nationalist distortion of Christianity wreak havoc on this country. I have little interest in the institutions of Christianity. BUT- since many Christian Nationalists are doing things I find antithetical to the life and teaching of Jesus, I refuse to give up the term. Institutional Christianity is a dumpster fire. But it is the dumpster fire that raised me, and so I am going to stake a claim and have an opinion about what it does. And particularly as Christian Zionism works to fund and animate so much settler violence in Palestine, I want to name myself as a Christian in the United States that stands against this. I reject the theology of Christian Zionism. I reject the extermination of the Palestinian people. I reject it being done in my name as an American and as a Christian. And I see and claim my Christian kin in Palestine.

I claim the term to push against these systems and theologies.

Social Justice Fundamentalism Is Bumming Me Out

Over the last 10 years I have walked with hundreds of WOC coming out of church trauma, queer folks ousted from their communities and churches, and women of color cut off from the churches that raised them. There has been a lot of pain. A lot of trauma. A lot of disillusionment.

But in the last few years, I have felt like I traveled far only to end up in the same place. Now instead of Christian Fundamentalism, I have entered the world of Social Justice fundamentalism. And it deeply concerns me. *

As of late, I’m often taken aback by the harshness of social justice people on social media. It’s mean. It’s eager to cut people off. It loves to critique. It thinks in extreme binaries. The church of social justice has ended up being more fundamentalist, conformist, and policing than any church I ever attended.

(And I grew up Seventh Day Adventist in the 80’s. Y’all don’t understand that reference. But just trust me. It’s a legit point I’m making. :)

In the Christian communities I was a part of, folks were so afraid of falling out of favor with church leaders and by extension God, that they tolerated spiritual abuse, affairs, exploitation, and toxic church cultures for years. But I think people are afraid in a different way now. Afraid that they will do or say something that will get them cut off, canceled, critiqued, or called problematic. And they are tolerating vitriol, meanness, and toxic community for fear of being ousted.

I have questions for us, questions for my beloved community, the larger network of folks who do social justice work, particularly online.

Questions about the world we are trying to build and the way we are doing it.

FUNDAMENTALISM ABOUNDS

Fundamentalism has some similar character traits no matter how it is being expressed. Here are some similarities between Christian Fundamentalism and Social Justice fundamentalism.

Strong binary thinking. Particularly viewing people as inside and outside

Punishment is being pushed out of community

People are disposable

There are deep schisms between people who essentially believe the same things. This expresses itself as denominations in Christianity and as ideological purity in social justice spaces.

Being right and feeling self righteous is an animating force in the community.

Disagreement is viewed as an existential threat.

They view the stakes as like and death

People remain fundamentally disposable. ( Yes, I said it twice.)

I have the same critique of Social Justice fundamentalism as I do of Christian Evangelicalism.

Christians will oust you don’t convert, if you don’t stay orthodox, if you stop being in “theological alignment.” They will argue that best way to let people know they are loved by Creator, is to tell them they are burning in hell, that God is angry at them, and that community will push them out if they don’t conform.

Social Justice Fundamentalism will oust you if you don’t agree, if you don’t perform emotional urgency about a particular issue, if you are not ideologically “pure” enough. They will challenge your worthiness as a person. And threaten to address it publicly on social media. Which is its own kind of hell.

We can’t say we’re fighting for a more just, healed, and liberated world, and then build that world by treating folks as disposable. We must resist the temptation to constantly draw lines in the sand and declare the people on the other side unclean.

For both groups the issues are life and death. Of the utmost urgency.

And both group betray the core of what is beautiful about their ethic. In the church of social justice we truly believe that every person is sacred, and should have the right to live. And not only to live, but to live with dignity, and hopefully joy.

However, more and more I encounter folks who want to learn more about certain justice issues, but are afraid to ask questions, afraid to learn, afraid to engage. Afraid that they will be shouted down for joining so late. Shamed for not caring sooner. Punished for not knowing more.

How do we hold space for urgency AND room for people to join later in the game.

How do we hold room for reality that justice work is both urgent AND a marathon?

How do we navigate the reality that the issue that you are passionately giving your life too, may not be the work someone else is doing? I have a friend whose mother is undergoing intense cancer treatment and she has been pouring herself out as a caretaker 7 days a week after working her full time job. She felt bad that she couldn’t do more around the situation in Palestine. I understood the sense of conflict. But should she feel bad? Isn’t caring for her very sick immigrant mom, also part of a healing ethic? It is also justice work and sacred work.

One of my core convictions is that HOW we do the work matters. It matters how we do Christianity. We can’t just talk about love, but then treat people like shit. And it matters how we do social justice work. We can’t say we are fighting for healing and liberation, and then leave a trail of people we consider disposable in our wake.

Deepa Iyer poses these two important questions in her book.

How can each of us contend with the urgency of this time with effectiveness, sustainability, and strong connections?

How can we embody grace, joy, and accountability even when the external forces of division and inequality are relentless?

I want us to explore these questions together. I want us to avoid the trap of having an analysis that is “so pure” we can no longer build together.

* I want to credit two articles I read that deeply shaped my thinking on this and that I consider this post to be in conversation with. Excommuicate Me from the Church of Social Justice- a blog by Francis Lee in 2017. And We Will Not Cancel Us by adrienne marie brown.

So You’re Thinking About Going Back To Church

Professor Ussama Makdisi ( Nephew of Dr. Edward Said)

This morning I attended a lecture at a Buddhist temple.

It felt familiar.

The gathering was on some old fold out chairs in a multi function room that I’m sure is used for school plays, gym time, and congregational meals.

I stood near the back listening to a lecture on Palestinian history.

Towards the end of the lecture I could see two white haired Japanese aunties and one grandpa setting out the food. Eventually they brought a silver kettle with tea to each table. We were told we could have lunch.

Nobody got in line.

About 5 minutes later one of the main teachers was invited to give a prayer and officially get us going into lunch. Folks finally started getting food.

—

It’s been a long time since I’ve slowly walked through the line for lunch in a church gym.

But it made me feel deeply nostalgic.

Growing up we used to have an all church potluck every Saturday after service.

I spent years eating dinner at my youth leader’s house.

And then grabbing lunch with friends after church as an adult.

There is a lot I don’t miss about church. But today I was reminded how many things I do miss.

I miss people, particularly a place to be together across generations.

I miss the conversation with folks who are different from me. Conversations with folks who think differently than me. And the way that our difference is handled with so much more gentleness and humanity in person versus online.

I miss the feeling of being taken care of by my elders. Fed. Even elders who don’t know me and that I don’t know. I felt held.

I felt nourished by the group ritual of everyone waiting to go through the potluck line until the third invitation.

I watched a boy carry a huge serving of food and a plate of doughnuts in a wobbly uneven fashion as he tried to move from where his mother put his food to where his friend’s were.

I miss all this.

I miss humans.

I miss being in the same room together.

There is something about the social media space that has worn me down in a profound way. I feel like people are yelling at me all the time. It feels so disembodied.

________

In 2020 and 2021 I met with countless WOC and folks who would tell me how shelter in place had given them the space they needed to leave church. Once everything moved online, they could just slip away, without the community conflict and scrutiny that would have come had everyone still been meeting in person.

They would almost whisper about the relief. The freedom of having their Sundays back. Not having to listen to pastors they no longer respected. Not having to have countless conversations defending and explaining themselves. Especially for Asian American women it was a welcome gift.

However, in the last year, I have noticed a shift.

In low tones, and apologetically, Women of Color/folks have started to talk about why they are thinking about going back to church.

The first reason has been kids. Folks know why they left in 2020. But as they are raising kids, they want their kids to have some kind of spiritual formation. They want their kids to know about God, to learn about Jesus. But they feel conflicted because they don’t want their kids to get the same version of Christianity that made them leave in 2020. But it also feels very difficult to guide kids spiritually without the support of a church.

I thought this cute photo of a drowsy Asian kiddo with chonky cheeks would be the least triggering of the many photo visuals I had to choose from.

(Someone could make a lot of money creating POC centered progressive children’s church curriculum right now. )

The second reason has been loneliness.

Folks have been lonely.

For a long time.

Finding community has been hard.

Especially in places that don’t have progressive churches.

And even then, a lot of progressive churches are mostly older white folks. And that has its own feeling of dissonance.

Women/ folks will be on zoom with me and almost apologetically say, “My husband and I are thinking about going back to church.”

Or.

“I don’t want to go back to church, but I don’t know what else to do.”

___

My thought is, it’s fine to go back.

And as is often talked about on the Bachelorette, it’s fine to be there for the wrong reasons.

For many of us, church used to be our entire social circle. We were there all day on Sundays, at small group during the week, maybe an additional leadership meeting. If you served on worship team, you were at rehearsal on another week night.

We left churches because they ousted us, told us God didn’t love us, gaslit our concern for justice. But we also left friends, people who showed up when we had babies, supported us when parents were sick. People to socialize with and take camping trips with. The joy of watching your kids in a giant jumble of other kids from church while the adults made dinner over camp stoves during the annual all church camping retreat.

Making friends as an adult is hard.

Finding people to date on apps is… perilous at times.

Everybody is there for the wrong reasons. ;)

For many who are thinking about going back to church, it isn’t to worship. It isn’t “for God.”

It’s for friends.

It’s for community.

It’s to find someone to date.

It’s to fill some of the loneliness that so many of us feel in 2024.

And frankly, I think that’s fine.

Some folks are a part of churches where they just attend on Sunday and that it is. They like the teaching, but they aren’t looking for more. Other’s are sort of putting up with the pulpit, for the chance to find humans to connect with in person. The loneliness is profound. The isolation. And using church as a sort of- institution that pre-screens people for you. That’s fine.

Many of us were told that you had to be ALL OUT for church as an expression of being ALL OUT for Jesus! But it is okay to be navigating this difficult, isolating landscape and figuring out what can work for you. I feel this particularly for folks who live in less diverse regions of the United States and Canada. Maybe you just show up for the church’s volunteer days and social activities and not for Sundays.

Maybe you find a small group that works for you.

And the truth is, you can always leave if it isn’t working out. If your nervous system rebels. If you realize that the pros still don’t outweigh the cons.

Or maybe you’ll find community at a Buddhist temple. Or with the universalists! Gasp!

On some level, it doesn’t matter.

Whether or not you go to church- I want you to be getting free from all the heteropatriarchal, colonial, white supremacist ideologies and frameworks that harmed so many of us. If you can do that while attending church, great.

What I can’t support a return to church as a sort of falling back asleep to reality. That would be a tragedy.

If you can’t go back to church. Because the only options are homophobic places that will not love you or let you be you. If you can’t go back, because the racism is too much, and the silence is too loud.

Can I invite you, invite us, to talk openly about the loneliness. The struggle to make friends as an adult. The grief of aloneness.

Loneliness is vulnerable to talk about.

But it is real.

Sometimes social media can help us find some of our people.

But more and more I think we need to acknowledge that it often makes us feel more alone and more unseen.

Loneliness can be embarrassing, sometimes crippling, but the truth is, it is profoundly human.

And feeling unsure where to turn and how to resolve it is something that I for one, can relate to deeply.

The lie they tell, is the truth about them

Yesterday I woke up to the horrifying image of a man holding a decapitated baby. An encampment in Rafah had been bombed, and we continue to witness the ruthless assault on the Palestinian people. The murder of children, the elderly, women, men continues before our eyes. And then we must watch as our government continue to send billions to Israel to enable this ongoing genocide. It makes it difficult to function on a daily basis.

Many of us will recall that Hamas was accused of beheading babies, and that misinformation was used as a catalyst to support Israel, Netanyahu, and the IDF. But today we have the photographic and video evidence that it is in fact Israel who commits this crime. And to be clear- Israel has long targeted and harmed children. The IDF has raped, tortured, imprisoned, and intentionally maimed Palestinians and specifically Palestinian children for decades.

Below are just a few articles on the topic.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/02/gaza-palestinian-children-killed-idf-israel-war

https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2024/01/26/palestine-is-disabled/

pnews.com/article/6035b1d3293c4a298145afbff50ab844

There are two dynamics at play that I wanted to discuss in this post.

When they talk about “THEM” they are talking about themselves.

I talk about this dynamic a lot when I train on white supremacy.

Whenever whiteness accuses a group of being something… they are telling on themselves.

They are describing who they are.

For example, for a long time white folks have perpetuated the stereotype that Black people are lazy. This from a group of people who literally institutionalized into the founding documents of this country the lifelong enslavement of African people, and their children, in perpetuity, so that they could be used for free labor. Whiteness was so greedy it created a new form of slavery that was never ending and passed on through birth. Who is lazy? The people who worked uncompensated for their entire lives, or the people who created an entire society dependent on the disgusting use of enslaved labor?

When slavery ended whiteness reinvented it, through sharecropping and incarceration.

A stereotype that whiteness likes to perpetuate about Black folks is that they break the law and commit crime at a high rate. But whiteness has simply written their stealing, exploitation, murder, and violence INTO the law. So that it can be committed daily, without consequences.

A fear narrative perpetrated by whiteness is that Black men are a threat to white women. This was prevalent in Jim Crow south. But it is white men who spent hundreds of years raping enslaved African women with impunity, and then raised their own children as slaves.

White folks talk about family values, while literally systemically and legally, breaking up Black and Indigenous families, making it legal to steal their children.

Whatever whiteness says about others, it is revealing about itself.

Whatever the oppressor says about those they oppress, they reveal about themselves.

Let’s bring it into the present. Here’s a little Trump quote from April 2024.

“ The Republican presidential candidate, appearing with several law enforcement officers, described in detail several criminal cases involving suspects in the country illegally and warned that violence and chaos would consume America if he did not win the Nov. 5 election.”

But who actually incited an insurrection after he was not re-elected? Trump. Who encouraged violence, and created actual chaos in the capital? Trump. The story he tells about immigrant, is the truth about himself.

Whiteness accuses undocumented people of committing crimes and stealing jobs from Americans. But wealthy men from the US, steal the most money, evade the most taxes, contribute the least to the collective good of society, exploit the most labor, and destroy the environment - because they have written the law, and the laws do not regulate their corporations. All the loopholes are created for them, and they will never be held accountable. Jail is not for those who break the law, it is for those who are Black.

When they said the college students were violent- they were talking about themselves

When they said the college students were breaking the law- they were talking about themselves

Whe say that the Palestinians are terrorists, they are talking about themselves.

Because they also said that Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Assata Shakur, BLM activists, and so many others were criminals and terrorists.

So.. point one, the oppressive regime, system, institution will always create a narrative about those they oppress. But that narrative is actually about themselves.

Their Agenda is power

People spend a lot of time trying to convince the oppressor that what they are doing is wrong. Y’all they know. They don’t care. Progressives often get so preoccupied with the idea that we need to convince them that they are wrong that we lose sight of their actual agenda. Power.

We are distracted by the myth.

Progressive folks are often distracted by their own sense of having the moral high ground, and the myth that those in power are at their core concerned with doing what is right. But for systems of power, the end goal is always- maintaining power. They have always rewritten the laws to maintain that end. The agenda is always dictated by that end. But progressives have a preoccupation with feeling righteous, and it can really distract from the work. ( This topic deserves its own post.)

Oppressive systems will, absolutely, destroy an institution the moment it no longer helps them maintain power- the supreme court, voting, term limits.

I say- systems of hierarchy, or systems of oppression, because I have found folks from the United States can get rigid or distracted when they see something happening and it doesn’t exactly fit into the language and frameworks they have been given for what is happening in the United States. I understand this, because I also did this.

A helpful pivot for me was when I started reading the book, The Trauma of Caste. When you read about a system of oppression that you are totally outside of, it brings clarity. My first reaction was, “Wow, how terrible! People are born into a caste and it shapes so much of their lives. How devastating.” But then I thought about Confucianism and what it has meant for women in Korea for hundreds and hundreds of years, and suddenly I could see it more clearly for what it is. Not with the blurred lines of a system that I was born into. I could see how being born a woman shaped the entire lives of Korean women. And I looked at the United States and the tolerance for people’s destiny being shaped by whether or not they are born Black or Native.

I started evaluating each situation, crisis, institution for the hierarchy it was creating, enforcing, and committed to. Whose destiny is set to oppression and death, simply by the group they were born into? Who actually has power in the system? How is the story being told to distract from that? When we look at Palestine and Israel, we see that Palestinians are destined for displacement, oppression, apartheid and likely, death.

The story of the oppressor is always that they are ethical, even benevolent, towards the ones they murder, rape, maim, and kill.

White people told this story about enslaving, raping, torturing African peoples in this country.

White people told this story about genociding Indigenous people across many continents.

Japanese people told the tale about occupying Korea.

England told this story about India.

White people told the story about incarcerating Japanese Americans.

Germans told this story about Jewish people.

Ok- this post has gone on way longer than I intended.

I simply wanted to make the point that

1- The story they tell about those they oppress, is the truth about themselves,

2- Power is the end goal. Getting it and maintaining it. We need to be more savvy and less distracted in our understanding what we are up against.